Nebenwirkungen

Unverträglichkeitsreaktionen unter IVIG sind insbesondere bei Erstgabe oder nach Wechsel des Präparates sehr häufig. Kopfschmerzen, Tachykardie, Flush, Übelkeit, Fieber oder Muskelschmerzen zählen hierbei zu den häufigsten Symptomen.Bei stärkerer Ausprägung dieser Zeichen kann es sich um eine anaphylaktoide Reaktion durch rasche Entstehung von Antikörper-Antigen-Komplexen oder gesteigerte Histamin-Ausschüttung handeln, im Gegensatz zu einer Anaphylaxie ohne arterielle Hypotension. Die Wahrscheinlichkeit einer solchen anaphylaktoiden Reaktion ist unter einer unkontrollierten Infektion erhöht. Auch die nicht gänzlich zu vermeidende Beimengung von Pre-Kallikrein, IgA und IgM, Gerinnungs- und Komplementfaktoren kann zu den genannten Nebenwirkungen beitragen. In der Regel nimmt von Infusion zu Infusion die Schwere der Akutreaktionen ab.

Die deutlich selteneren späten Nebenwirkungen auf die Gabe von IVIG umfassen venöse sowie arterielle thromboembolische Ereignisse aufgrund der hohen Viskosität der Präparate. Auch Fälle von akuter Niereninsuffizienz wurden berichtet.

Um die genannten Nebenwirkungen zu vermeiden, wird neben einer ausreichenden Hydratation eine eingangs niedrige Infusionsrate mit allmählicher Steigerung empfohlen. In manchen Fällen kann eine prophylaktische Begleitmedikation indiziert sein, z.B. mit Dimetinden und Paracetamol. Kommt es dennoch zu einer Unverträglichkeitsreaktion, können nach Pausieren der Infusion weitere Antihistaminika, Glukokortikoide oder NSAR verabreicht werden.

Nach Gabe von SCIG sind systemische Nebenwirkungen deutlich seltener. Lokale Entzündungsreaktionen sind indes möglich.

Nach Gabe parenteraler Immunglobuline kann häufig eine veränderte Virus-Serologie gesehen werden ebenso wie falsch positive Serum-Marker wie ANA, ANCA und RF oder auch ein positiver direkter Coombs-Test ohne Zeichen einer Hämolyse. Dies sollte sich üblicherweise innerhalb von 60 Tagen nach Gabe normalisieren. IgM-Assays sind nicht betroffen.

Therapieempfehlung

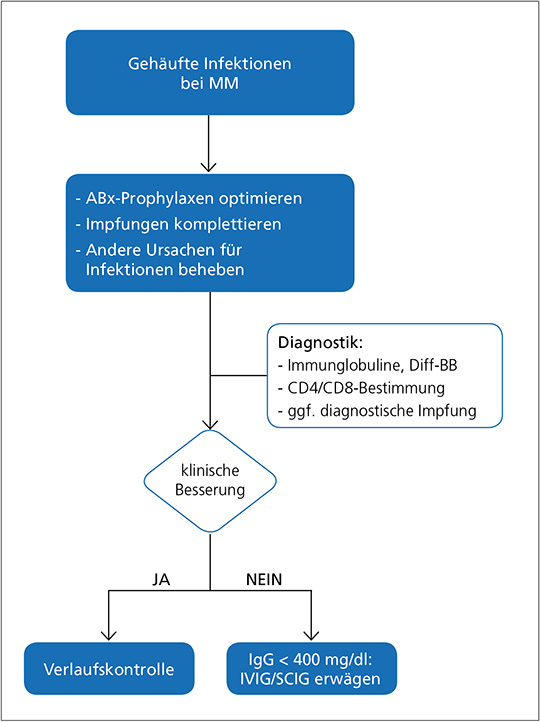

Die Therapieempfehlungen zur Immunglobulin-Substitution sind individuell am Patienten auszurichten. So ist bei Patienten mit Hypogammaglobulin-ämie und seltenen Infektionen unter angemessenen Prophylaxen oder bei Patienten mit ausreichender Impfantwort eine abwartende Haltung vertretbar.Bei gehäuften Infektionen mit unzureichender Wirkung der antiinfektiven Prophylaxen, Fehlen einer serologischen Impfantwort und ausgeprägter Hypogammaglobulinämie (IgG < 400 mg/dl) kann allerdings die parenterale Gabe von Immunglobulinen erwogen werden (Abb. 4) (43).

Falls klinisch indiziert, sollte eine aktuelle Serologie für CMV, EBV und HBV noch vor Behandlungsbeginn erhoben werden ebenso wie ein metabolischer Status einschließlich Transaminasen und Serum-Kreatinin.

Die Anfangsdosis sollte 0,4-0,5 g/kg alle 4 Wochen (IVIG) oder 0,1-0,2 g/kg pro Woche (SCIG) betragen. IVIG führen zu einem raschen Spiegelanstieg und zeigen pharmakokinetisch eine Halbwertszeit von ca. 28-30 Tagen. Nach Gabe von SCIG kommt es erst nach 36-72 Stunden zum Spitzenspiegel. In Verbindung mit der meist wöchentlichen Gabe führt dies zu einer gleichmäßigeren Verteilung der IgG-Konzentration unter SCIG.

Eine Dosisanpassung kann je nach klinischem Ansprechen und IgG-Talspiegel erfolgen, wobei orientierend ein Talspiegel von > 400 mg/dl IgG und das Ausbleiben gehäufter Infektionen als Ziel formuliert werden kann.

Es besteht kein Interessenkonflikt.

Zu diesem Artikel ist auch ein CME-Test verfügbar.

Hier kommen Sie direkt zur Teilnahme(verfügbar bis zum 28.09.2021)

Facharzt

Medizinische Klinik 2, Hämatologie und Onkologie, Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt

Theodor-Stern-Kai 7

60590 Frankfurt am Main

david.zurmeyer@kgu.de

| Dr. med. univ. Ivana von Metzler Fachärztin Medizinische Klinik 2 Hämatologie, Onkologie Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt Theodor-Stern-Kai 7 60590 Frankfurt am Main E-Mail: ivana.metzler@kgu.de |

D. Zurmeyer, I. v. Metzler, Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt.

Infection is a leading cause of death for patients with Multiple Myeloma (MM). Cellular immune dysfunction is characterized by numerical and functional deficiencies of lymphocytes, NK cells and dendritic cells as well as by treatment-related neutropenia. Humoral immunity is compromised by hypogammaglobulinemia in 87% of patients with symptomatic MM and can often be seen after autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). A detailed workup of immune parameters should be sought in patients with MM or after ASCT with recurrent infection despite adequate antimicrobial prophylaxis. Completion of vaccinations is recommended according to guidelines. Also, a diagnostic immunization is a useful means of determining a patient’s ability to mount an immune response. If severe hypogammaglobulinemia is shown (i.e. IgG < 400 mg/dl) in a patient with recurrent infections despite antimicrobial prophylaxis a trial of intravenous Ig (IVIG) or subcutaneous Ig (SCIG) is recommended.

Keywords: Multiple Myeloma, cellular immune dysfunction, ASCT, hypogammaglobulinemia

(1) Cowan AJ, Allen C, Barac A et al. Global Burden of Multiple Myeloma: A Systematic Ana- lysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1221.Global.

(2) Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood 2009;113(22):5412-5417.

(3) Tete SM, Bijl M, Sahota SS et al. Immune defects in the risk of infection and response to vaccination in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and multiple mye- loma. Frontiers in immunology 2014;5:257.

(4) Augustson BM, Begum G, Dunn JA et al. Early mortality after diagnosis of multiple myeloma: analysis of patients entered onto the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials between 1980 and 2002 – Medical Research Council Adult Leukaemia Working Party. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(36):9219-26.

(5) Kristinsson SY, Tang M, Pfeiffer RM et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and risk of infections: a population-based study. Haematologica 2012;97(6):854-8.

(6) Teh BW, Harrison SJ, Worth LJ et al. Risks, severity and timing of infections in patients with multiple myeloma: a longitudinal cohort study in the era of immunomodulatory drug therapy. British Journal of Haematology 2015;171(1):100-8.

(7) Nucci M, Anaissie E. Infections in patients with multiple myeloma in the era of high-dose therapy and novel agents. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009;49(8):1211-25.

(8) Blimark C, Holmberg E, Mellqvist U-H et al. Multiple myeloma and infections: a population-based study on 9253 multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica 2015;100(1):107-13.

(9) Friman V, Winqvist O, Blimark C et al. Secondary immun- odeficiency in lymphoproliferative malignancies. Hematological Oncology 2016;34(3):121-32.

(10) Kastritis E, Zagouri F, Symeonidis A et al. Greek Myeloma Study Group. Preserved levels of uninvolved immunoglobulins are independently associated with favorable outcome in patients with symptomatic multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2014;28(10):2075-2079.

(11) Seppänen M. Immunoglobulin G treatment of secondary immunodeficiencies in the era of novel therapies. Clinical and experimental immunology 2014;178(Suppl 1):10.

(12) Heaney JL, Campbell JP, Iqbal G et al. Characterisation of immunoparesis in newly diagnosed myeloma and its impact on progression-free and overall survival in both old and recent myeloma trials. Leukemia 2018;32(8):1727.

(13) Jolles S, Chapel H, Litzman J. When to initiate immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IGRT) in antibody deficiency: a practical approach. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 2017;188(3):333-41.

(14) Stahn C, Buttgereit F. Genomic and nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids. Nature Re- views Rheumatology 2008;4(10):525.

(15) Wirsum C, Glaser C, Gutenberger S et al. Secondary antibody deficiency in glucocorticoid therapy clearly differs from primary antibody deficiency. Journal of clinical immunology 2016;36(4):406-12.

(16) Kado R, Sanders G, McCune WJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia after rituximab therapy. Current opinion in rheumatology 2017;29(3):228-33.

(17) Mateos M-V, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M et al. Daratumumab plus bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med 2018;378(6):518-28.

(18) Dimopoulos MA, Dytfeld D, Grosicki S et al. Elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2018;379(19):1811-22.

(19) Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2005;352(24):2487-98.

(20) Alexander T, Sarfert R, Klotsche J et al. The proteasome inhibitior bortezomib depletes plasma cells and ameliorates clinical manifestations of refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2015;74(7):1474-8.

(21) Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med 2014;371(10):906-17.

(22) Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012;366(19):1782-91.

(23) Dimopoulos MA, Swern AS, Li JS et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with relap- sed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J 2014;4:e257.

(24) Ravi P, Kumar S, Gonsalves W et al. Changes in uninvolved im- munoglobulins during induction therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood cancer journal 2017;7(6):e569.

(25) Sonis ST, Oster G, Fuchs H et al. Oral mucositis and the clinical and economic outcomes of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2001;19(8):2201-5.

(26) Guillaume T, Rubinstein DB, Symann M. Immune reconstitution and immunotherapy after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 1998;92(5):1471-90.

(27) Small TN, Keever CA, Weiner-Fedus S et al. B-cell differentiation following autologous, conventional, or T-cell depleted bone marrow transplantation: a recapitulation of normal B-cell ontogeny. Blood 1990;76(8):1647-56.

(28) Bengtsson M, Smedmyr B, Festin R et al. B lymphocyte regeneration in marrow and blood after autologous bone marrow transplantation: increased numbers of B cells carrying activation and progression markers. Leukemia research 1989;13(9):791-7.

(29) Schütt P, Brandhorst D, Stellberg W et al. Immune parameters in multiple myeloma patients: influence of treatment and correlation with opportunistic infections. Leukemia & lymphoma 2006;47(8):1570-82.

(30) Patel SY, Carbone J, Jolles S. The Expanding Field of Secondary Antibody Deficiency: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Frontiers in immunology 2019; doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00033.

(31) Srivastava S, Wood P. Secondary antibody deficiency–causes and approach to diagnosis. Clinical Medicine 2016;16(6):571-6.

(32) Rieger CT, Liss B, Mellinghoff S et al. Anti-infective vaccination strategies in patients with hematologic malignancies or solid tumors Guideline of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann Oncol 2018;29(6):1354-65.

(33) Drayson MT, Bowcock S, Planche T et al. Tackling Early Morbidity and Mortality in Myeloma (TEAMM): Assessing the Benefit of Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Its Effect on Healthcare Associated Infections in 977 Patients. Blood 130.Suppl 1 (2017):903.

(34) Niehues T, Bogdan C, Hecht J et al. Impfen bei Immundefizienz. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz. 2017;60(6):674-84.

(35) Imbach P, d‘Apuzzo V, Hirt A et al. High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in childhood. Lancet 1981;317(8232):1228-31.

(36) Furusho K, Nakano H, Shinomiya K et al. High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin for Kawasaki disease. Lancet 1984;324(8411):1055-8.

(37) Buckley RH, Schiff RI. The use of intravenous immune globulin in immunodeficiency di- seases. N Engl J Med 1991;325(2):110-7.

(38) Chapel HM, Lee M, Hargreaves R et al. Randomised trial of intra-venous immunoglobulin as prophylaxis against infection in plateau-phase multiple myeloma. Lancet 1994;343(8905):1059-63.

(39) Musto P, Brugiatelli M, Carotenuto M. Prophylaxis against infections with intravenous immunoglobulins in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 1995;89(4):945-6.

(40) Park S, Jung CW, Jang JH et al. Incidence of infection according to intravenous immunoglobulin use in autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with multiple myeloma. Transplant Infectious Disease 2015;17(5):679-87.

(41) Blombery P, Prince HM, Worth LJ et al. Prophylactic intra-venous immunoglobulin during autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma is not associated with reduced infectious complications. Annals of hematology 2011;90(10):1167-72.

(42) Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: a global perspective. Bone marrow transplantation 2009;44(8):453.

(43) Ueda M, Berger M, Gale RP et al. Immunoglobulin therapy in hematologic neo-plasms and after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Rev 2018;32:106-15.

Sie können folgenden Inhalt einem Kollegen empfehlen:

"Hypogammaglobulinämie beim Multiplen Myelom 06/2019"

Bitte tragen Sie auch die Absenderdaten vollständig ein, damit Sie der Empfänger erkennen kann.

Die mit (*) gekennzeichneten Angaben müssen eingetragen werden!